Harris Detector

Published:

Widely used for corner detection in computer

Harris Detector

Widely used for corner detection in computer vision. Corners, as distinctive image features, are particularly important because they provide stable points that can be tracked between images. See Locating and Describing Interest Points

To fully understand the Harris corner detection, we’ll break down the math behind it and touch on concepts like eigenvalues and eigenvectors.

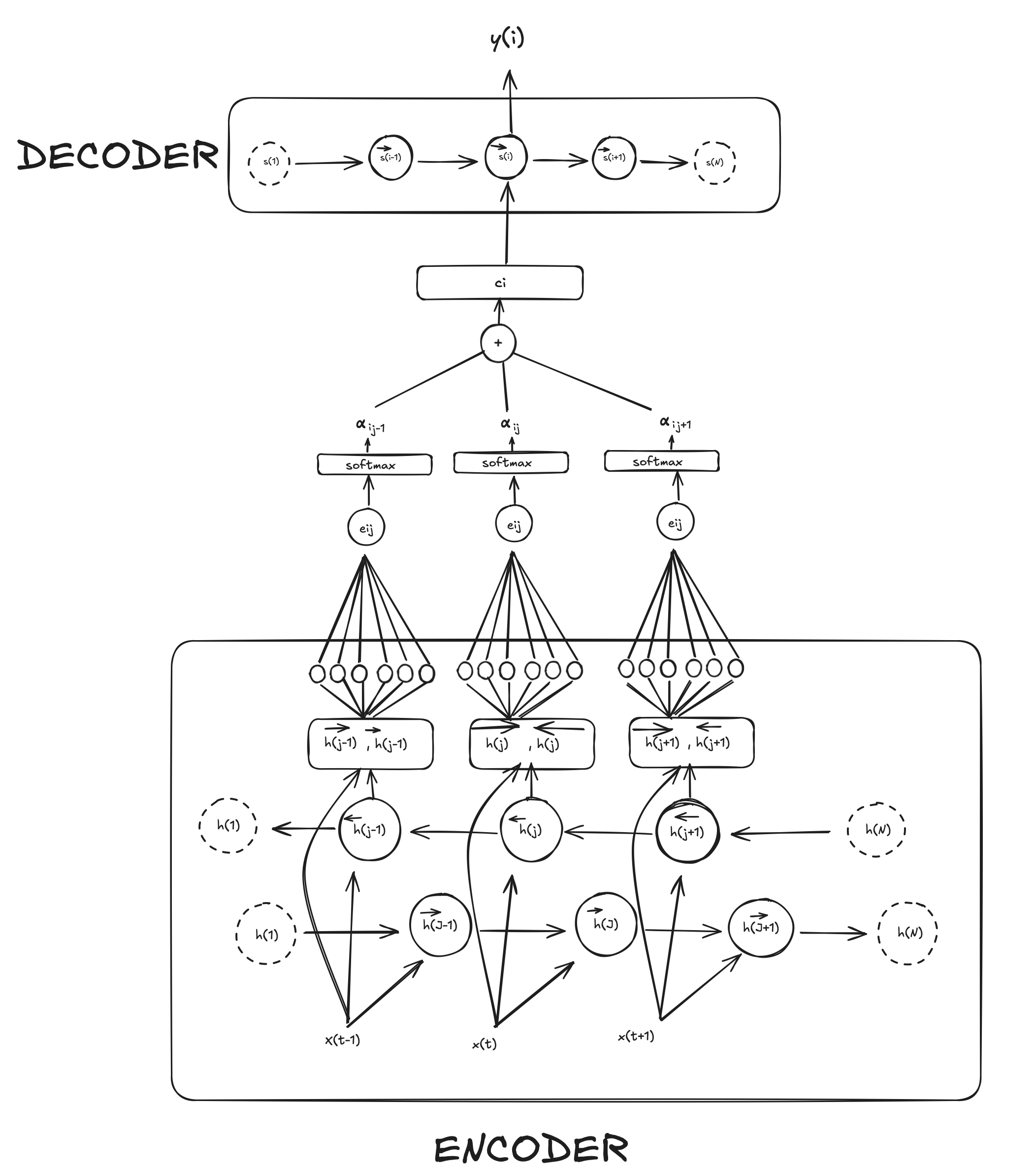

1. Second Moment Matrix (Auto-correlation Matrix)

At the heart of the Harris detector is the second moment matrix, also called the structure tensor. This matrix contains information about local image gradients (changes in pixel intensities) and captures how the intensity changes in a small neighborhood around a pixel.

The matrix is formed from the partial derivatives of the image intensities with respect to $x$ and $y$:

$I_x$ is the partial derivative of the image in the x-direction (horizontal edge information). $I_y$ is the partial derivative in the y-direction (vertical edge information).

The second moment matrix is denoted as:

\[\mathbf{M} = \begin{bmatrix} I_x^2 & I_x I_y \\ I_x I_y & I_y^2 \end{bmatrix}\]To obtain this matrix over a neighborhood (not just at a single pixel), we smooth the gradients by applying a Gaussian filter. In other words, the matrix $\mathbf{M}$ gets smoothed by the Gaussian filter $g(\sigma_I)$ to produce a final matrix $\mu(\sigma_I,\sigma_D)$. This matrix contains the weighted sum of the gradient information over a neighborhood, allowing us to assess the cornerness of a region.

\[\mu(\sigma_I,\sigma_D) = g(\sigma_I)*\begin{bmatrix} I_x^2(\sigma_D) & I_x I_y (\sigma_D) \\ I_x I_y(\sigma_D) & I_y^2 (\sigma_D)\end{bmatrix}\]$Ix(σ_D)$ and $I_xy(\sigma_D)$ These are the partial derivatives of the image in the $x$- and $y$-directions, but they are computed after smoothing the image using a Gaussian filter of scale $\sigma_D$. The notation $I_x(\sigma_D)$ means the derivative was computed on an image that has been smoothed using a Gaussian filter with standard deviation $\sigma_D$ often referred to as derivative smoothing.

Gaussian filter $g(\sigma_I)$: After the derivatives are computed, we apply another Gaussian filter of standard deviation $\sigma_I$, which is often referred to as integration scale. This filter smooths the second moment matrix (i.e., the matrix of squared gradients) over the local neighborhood of each pixel.

Why two Different Scales: $\sigma_D$ and $\sigma_I$?

$\sigma_D$ This scale controls how finely the gradients are computed. A smaller $\sigma_D$ will pick up finer details of the image, making the derivatives more sensitive to small, fine edges or textures. A larger $\sigma_D$ will blur the image more, resulting in coarser derivatives.

$\sigma_I$: This scale controls how much smoothing is applied to the matrix of squared gradients $\mathbf{M}$ A larger $\sigma_I$ will average the gradient information over a larger neighborhood, making the feature detection (i.e., corner detection) more robust to noise, but possibly less responsive to fine detail.

This distinction is important because the image structure (edges, corners, textures) can appear at different scales. For instance, you might want to compute derivatives on a finely detailed image ($\sigma_D$) but smooth the results over a larger area ($\sigma_I$) to avoid being too sensitive to noise or local irregularities.

2. Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors

To understand why we use eigenvalues, let’s first explain what they are.

- Eigenvectors are directions in which a linear transformation acts by only scaling them (i.e., their direction doesn’t change).

- Eigenvalues are the scaling factors corresponding to those eigenvectors.

The eigenvalues of the matrix $\mu(\sigma_I, \sigma_D)$ (which is essentially a smoothed version of the second moment matrix) represent the intensity variations in the $x$- and $y$-directions after both derivative computation and smoothing. These eigenvalues are essential for distinguishing between corners, edges, and flat regions:

- If both eigenvalues are large, this indicates a corner (significant intensity change in both directions).

- If one eigenvalue is large and the other is small, this indicates an edge (intensity changes mainly in one direction).

- If both eigenvalues are small, this indicates a flat region (little or no intensity change in any direction).

So, the eigenvalues give us a measure of how the image gradients behave in a neighborhood. For corner detection, we are interested in areas where the intensity changes significantly in both directions, which corresponds to both eigenvalues being large.

3. Cornerness Function

The Harris detector doesn’t explicitly compute the eigenvalues but instead uses an approximation based on the determinant and trace of the matrix $\mathbf{M}$ to determine corner strength.

\[\begin{align*} har &=det[\mu(\sigma_I,\sigma_D)]−α⋅ [trace(\mu(\sigma_I,\sigma_D))^2] \\&= g(I^2_x)g(I^2_y) - [g(I_xI_y)]^2 - \alpha[g(I^2_x) + g(I^2_y)]^2 \end{align*}\]Harris Detector: Mathematics

- We want large eigenvalues, and small ratio. The eigenvalues need to be strong in both axes. We can capture that with this function with the a function that combines the determinant and the trace

- We know:

- Harris detector defined via

k: empirical constant, k= 0.04-0,06 t: threshold

Comments